An interesting article in the New Yorker called The Open Office Trap makes a solid case for carefully considering whether an open plan office is right for your business. I still think that for some, it definitely is.

Very few things have a “one size fits all”: it’s unlikely that a particular setup is best for all organisations. In addition, business can have arrangements tailored to the needs of a particular department, and even individual people. Some people work best in a little cocoon, while others thrive in a group.

With the new need to also (re)arrange offices to enable social distancing (re COVID-19), this would generally be simpler and more economic in an open plan rather than a segmented office. With open I don’t mean a cubicle farm, you want sufficient space between people and desks.

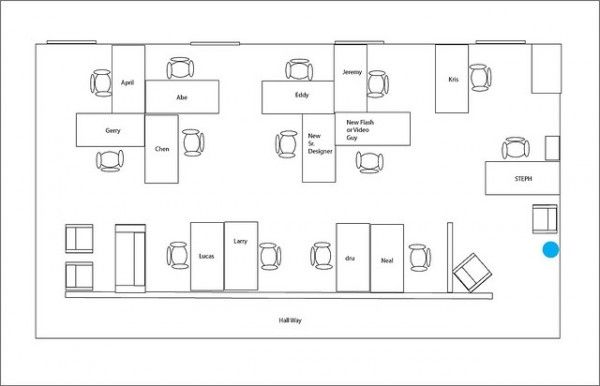

I was in charge of configuring a new office space late last year, and it seems that that has worked out really well (even taking new social distancing needs into account). Naturally some aspects are specific to the space you need to work with, but there are some general guidelines that would apply in most places.

Looking “cool” should never be a primary consideration when thinking about office layout. I’ve seen many cool looking offices that are entirely unpractical. What’s the point?

On average, you need about 10m² per person, so if you have 100m², that will fit about 10 people. That doesn’t mean that everyone has a space of 10m² around them, but with walkways and other common areas, it should just about work out.

Two desks facing each other, or islands with 3 or 4 desks, tends to work fairly well. More than two desks in a row tends to cause issues.

Desk sharing is a bad idea, it really frustrates people and stresses them out – it can be acceptable as a very temporary solution when a workforce is growing, but really for no longer than a few months.

It is important to consider the space behind people, so there is enough room for people to walk by (or in between), or for instance for someone to use a sit-stand desk arrangement (which will see them stand back a bit further than where they’d be when they sit).

Some people may need to hide in a corner or have their own little space (with or without a door). That is often easily accomplished, and it is definitely part of the original open plan office concept.